COLE THALER | August 28, 2018

The word “race” does not appear in AVLF’s mission statement or vision statement, but there’s no question that the work we do on behalf of low-income tenants is racial justice work. Here’s why.

1. Housing inequality in Atlanta is not race-neutral.

In a 2016 paper, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta found that Atlanta’s high eviction rate is spatially concentrated in predominantly Black neighborhoods. The authors concluded that “the households bearing the brunt of the extremely high housing instability in Atlanta live in predominantly Black neighborhoods.”

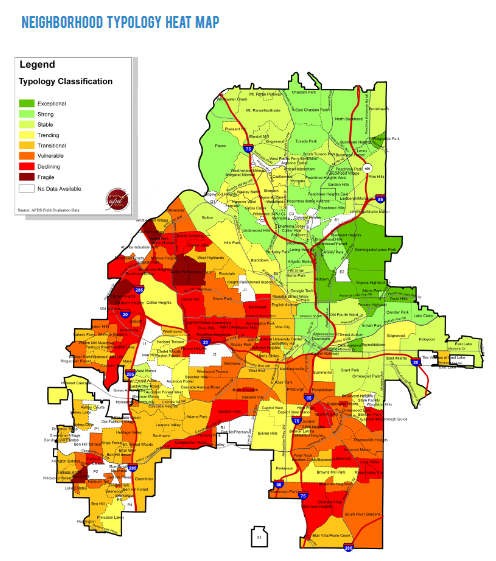

The problem is bigger than just evictions. The Atlanta neighborhoods with the highest proportions of blighted housing – that is, dilapidated or abandoned structures, often owned by neglectful or absentee landlords – include Grove Park, English Avenue, and Pittsburgh, and are disproportionately inhabited by Black residents. Atlanta’s recent Strategic Community Investment report contains a detailed analysis of the city’s residential housing stock and shows heavy concentrations of “vulnerable,” “declining,” and “fragile” housing in the city’s Black West and South neighborhoods, whereas the whiter neighborhoods in North and East Atlanta are characterized by “exceptional,” “strong,” and “stable” housing.

The problem extends to those who have no housing. Research conducted by the Center for Social Innovation’s SPARC initiative found that, while 53.5% of Atlanta’s population is Black, more than 87% of Atlanta’s homeless population is Black.

In short, you cannot work for housing fairness in our city and be color-blind.

In short, you cannot work for housing fairness in our city and be color-blind.

These statistics are borne out by AVLF’s internal demographic data, which show that more than three-quarters of our Safe & Stable Homes Project clients are Black. A visit to the Fulton County Courthouse on dispossessory days routinely features a sea of Black faces, fighting to stay housed.

In short, you cannot work for housing fairness in our city and be color-blind. The Atlantans most hurt by our housing disparities are disproportionately Black, and our Black neighbors stand to benefit from our efforts toward housing justice.

2. Housing laws and policies have historically been used as a tool of white supremacy.

Race-based housing injustice in Atlanta is nothing new. In 1936, a predominantly Black shantytown known as Tech Flats was bulldozed to make room for the nation’s first public housing project, a whites-only development known as Techwood Homes. Racial segregation in Atlanta’s public housing projects persisted for many years.

Similarly, Kennesaw State University Professor Jason Rhodes has written about the 1938 Home Owners Loan Corporation map, which divided Atlanta by neighborhoods and marked the ones with high Black populations as being “hazardous” places to underwrite mortgages.

But these practices were not unique to Atlanta. In his book The Color of Law, Richard Rothstein documents numerous racially explicit government policies – federal, state, and local — that promoted and enforced racial segregation in housing. Ranging from racially-restrictive covenants to discriminatory zoning to redlining and beyond, the examples catalogued in Rothstein’s book leave no doubt that housing laws and policies have long been powerful tools of racism. Moreover, their effects persist today in every segregated neighborhood, even where the problematic laws and policies themselves have been erased.

The work of AVLF and our partners to address housing disparities necessarily plays out against this racialized background, and directly responds to and challenges it.

3. Poverty in general takes a heavier toll on communities of color, and so working to end poverty is working for racial justice.

Finally, it is well-established that poverty rates are higher in communities of color – especially in Black and non-white Hispanic communities. In 2017, the U.S. Census Bureau released data showing that 22% of Black households live in poverty, whereas only 8.8% of non-Hispanic whites live in poverty. According to the Center for Social Innovation’s SPARC report, while 53.5% of Atlanta’s population is Black, nearly 76% of those living in deep poverty are Black. Black people living in poverty are less likely than others to move up the economic ladder, due to the effects of discrimination, educational inequalities, mass incarceration, and other factors.

Put simply, AVLF sees poverty as a kind of racial injustice, and our work to end poverty for our clients is a step towards racial equity.

At its core, AVLF’s work to stop evictions, get repairs made, and otherwise promote housing stability is intended to reduce poverty and increase the likelihood that our impoverished clients will reach their full potential, unrestricted by economic barriers. And because poverty in our city and country is inextricably bound up with race discrimination, our attacks on poverty are attacks on poverty’s racist tactics and effects. Put simply, AVLF sees poverty as a kind of racial injustice, and our work to end poverty for our clients is a step towards racial equity.

To be sure, all races are harmed by poverty, and AVLF has clients of all races. Mold does not care about the race of the tenants it harms, and slumlords don’t, either – and AVLF thrives on fighting slumlords (and mold!). But it is disingenuous to look upon the uneven landscape of Atlanta’s housing crisis and leave race out of the conversation. Worse, it undermines our efforts toward justice if we proclaim colorblindness, or avoid discussing race because those discussions can be uncomfortable. Instead, we must open our eyes to poverty in all its brutality. We must affirm that housing disparities, poverty, and racism are equally unwelcome in the just world that we are building together.

Learn how we’re fighting for justice with our place-based program, Standing with Our Neighbors™.

Cole Thaler

Director, Safe & Stable Homes Project

Check out more from this author.

Cole serves as the director of AVLF’s Safe and Stable Homes Project. He oversees the Saturday Lawyer Program and the Standing with Our Neighbors Program, among others.

Before joining AVLF, Cole was a supervising staff attorney with Georgia Legal Services Program, where he represented low-income rural Georgians in a variety of civil matters. Previously, Cole worked for Lambda Legal, a national legal organization that works on behalf of lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, transgender people, and those with HIV. Cole attended Williams College before receiving his J.D. from Northeastern University School of Law. He shares his home with two rescue dogs, three rescue cats, and husband.